Responsible Contracting in Sustainable Procurement

Introduction: What is responsible contracting?

Definition of responsible contracting

Responsible contracting refers to the practice of integrating human rights and environmental (HRE) obligations into commercial contracts in a way that commits both parties to work together to uphold HRE standards.

While there is no one-size-fits-all contractual template for every context, the responsible contracting approach, also referred to as the shared-responsibility approach, can be applied to any type of contract, including contracts for the sale and manufacturing of goods, services, financing, licensing, franchising and carbon offsets, among others.

The responsible contracting approach is also sector-agnostic, meaning it can apply to any supply chain. A key feature of responsible contracts is that they align with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct (OECD Guidelines).

Generally, this means that responsible contracts are designed to integrate and support effective human rights and environmental due diligence (HREDD) as set out in the UNGPs and the OECD Guidelines. More specifically, it means that responsible contracts operationalise the shared-responsibility principles enshrined in the UNGPs and the OECD Guidelines.

Learn more

To learn more about the human rights due diligence process, UN Global Compact participants can join the Business & Human Rights Accelerator – a six-month programme activating companies across industries and regions to swiftly move from commitment to action on human rights and labour rights through establishing an ongoing human rights due diligence process.

The core principles of responsible contracting

According to the Responsible Contracting Project (RCP), three core principles animate responsible contracting and distinguish it from traditional contracting.

These principles, referred to as the “3 Rs” of responsible contracting are:

Responsible contracts set aside unrealistic and dangerous guarantees of perfect compliance by one party (usually the supplier) and instead commit both parties to work together to uphold HRE standards and to cooperate in carrying out ongoing, risk-based HREDD.

Responsible contracts commit the buyer to engage in responsible purchasing practices, which is critical for effective HREDD. They also commit the supplier to engage in responsible purchasing practices with its own suppliers and sub-contractors.

In the event of an adverse HRE impact, responsible contracts place HRE remediation ahead of traditional contract remedies such as suspending payments, canceling orders and termination.

Remediation focuses not on the contract parties, but rather on the victims of the impact — the workers and their communities. HRE remediation includes putting an end to the impact, addressing its root causes to ensure it does not reoccur and addressing the grievances of the victims.

Exit due to an adverse HRE impact can contractually only be pursued as a last resort, if it becomes clear that remediation efforts are not or cannot be successful. If exit is pursued, it must be done responsibly, weighing the adverse impacts of exit against those of staying and taking measures to mitigate them.

The shortcomings of traditional contracting

Contracts, along with supplier codes of conduct, are the most widely used tool for managing supply chain risks, including human rights and environmental (HRE) risks.

Contracts take a company’s HRE policies, which, on their own, are usually unenforceable and make them binding. Contracts make it possible for companies to implement their HRE policies and standards, in a legally binding fashion, across borders and throughout their supply chains.

This explains why companies rely so heavily on their contracts: Contracts give companies a legal tool to police their supply chains, even in the absence of national legislation — or, as is often the case, in the absence of enforced national legislation. Plus, unlike national legislation, contracts are legal documents that the companies can shape and control directly.

Unfortunately, while contracts are widely used to manage supply chain risks, they are often mis-used to manage human rights and environmental (HRE) risks. When buyer companies include HRE obligations in their agreements with suppliers, they often place all the risks, obligations and costs associated with upholding HRE standards on the supplier. This is because traditional contracts focus on managing company risks, not HRE risks. The company-risk focus encourages using the contract to remove as much risk as possible from the buyer’s side of the contractual balance sheet and to place as much of it as possible on the supplier’s side. To achieve this, traditional contracts rely on supplier-only guarantees of perfect compliance with HRE standards and punish imperfection with order cancellations, suspension of payments and contract termination.

To formalize risk-shifting, suppliers are often required to make a contractual promise (by way of a representation or a warranty) that there are no HRE violations anywhere in the supply chain. Such promises are unrealistic — there is no such thing as a perfectly clean supply chain, so to include perfection as a contractual obligation often places the supplier in breach on day one. Not only are these promises unrealistic, but they are also dangerous because they incentivize suppliers to hide infractions out of fear of losing the contract. This pushes infractions further out of the buyer’s view, where they are even less likely to be identified, let alone addressed or remediated. In other words, risk-shifting, expecting perfect compliance and punishing imperfection can actually aggravate HRE risks by incentivizing deception, disincentivizing transparency and making it much harder to address HRE problems, which are bound to arise.

Understanding how contracts are often misused to manage HRE risks.

While risk-shifting may be effective for some aspects of supply chain risk management, it is ineffective for the purposes of managing human rights and environmental (HRE) risks. When it comes to preventing adverse HRE impacts, risk-shifting is not the same thing as risk management.

Human rights and environmental due diligence (HREDD) requires identifying and addressing HRE risks through ongoing, risk-based, proactive engagement. HREDD does not outlaw imperfection but rather accommodates it as a matter of course. Traditional contracts that formalize a legal fiction of perfect compliance set the supplier up for failure and incentivize non-transparency and non-compliance. This is why traditional contracts are not fit for purpose when it comes to managing HRE risks in global supply chains.

For HREDD to be effective, companies should move away from the traditional one-sided, strict compliance model of contracting toward a due diligence-aligned model that is cooperation-based, dynamic, responsive and supported by responsible purchasing practices.

Understanding why risk-shifting is ineffective for managing HRE risks in supply chains.

Case examples: implementing responsible contracts

A global shipping liner company published a new supplier code of conduct (SCoC) in 2023 that reflects several of the core principles of responsible contracting, including shared responsibility (described as “joining forces”) between buyers and suppliers to prevent adverse impacts and take remedial action in the event of an adverse impact, a commitment to responsible purchasing practices and a commitment to responsible exit.

A Swedish brand that sells bags and backpacks has contracts with suppliers that incorporate a responsible exit strategy and emphasize a commitment to paying fair prices. The contracts also include prompt payment terms and hold the brand financially responsible for leftover materials and unsold stock. Through these contracts, the brand strives to share the responsibility with suppliers for transparency, fair pricing, social sustainability and human rights due diligence.

The difference between traditional contracting and responsible contracting

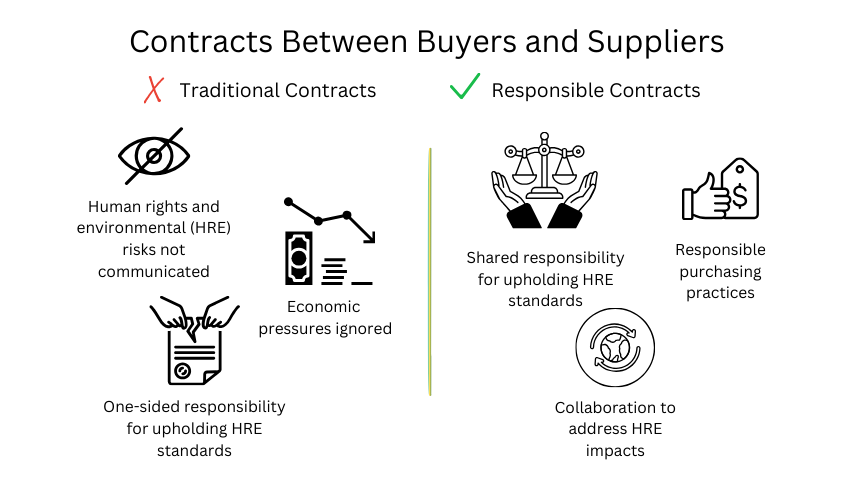

The main distinction between traditional and responsible contracting lies in how the contract is structured. Traditional contracts place HRE-related risks and obligations solely on the supplier but responsible contracts include and operationalize a shared responsibility by both parties to work together to uphold HRE standards.

Here is how this structural distinction plays out in practice:

With responsible contracts, each party contractually commits to cooperate in carrying out human rights and environmental due diligence (HREDD) in a realistic and fair manner, assuming reasonable and appropriate risks and costs.

The buyer commits to engaging in responsible purchasing practices that support the supplier’s human rights and environmental (HRE) performance. Traditional contracts do not typically include any obligations for the buyer to adjust their purchasing practices to uphold HRE standards. In fact, by placing all the responsibility on the supplier, traditional contracts allow the buyer to overlook the reality that their own behaviour can seriously affect HRE outcomes.

As the Better Buying Institute has shown, purchasing practices have a significant impact on workers’ rights and well-being. Poor purchasing practices include, for example, imposing prices that do not cover production costs, too-short delivery timelines but too-long payment terms, inaccurately forecasting needs, changing orders without adjusting time or price terms and awarding contract renewals solely based on the lowest price.

These practices can create serious commercial pressures on suppliers, which are then passed on to workers and their communities. This is why it’s important to include a commitment to responsible purchasing practices as part of the buyer’s human rights and environmental due diligence (HREDD) obligations.

The last fundamental distinction between responsible and traditional contracts is that, whereas traditional contracts treat imperfect compliance with human rights and environmental (HRE) standards as a breach of contract that activates the buyer’s right to suspend payments, cancel orders and terminate the contract, responsible contracts place HRE remediation ahead of remedies for the parties.

In other words, responsible contracts are structured to ensure that the people harmed by an HRE infraction or violation see their grievances addressed as a matter of priority.

Responsible contracting in action

These example model contract clauses (specific language suggestions) to include in your contracts are based on the Model Contract Clauses 2.0 and the draft European Model Clauses (EMCs) for Responsible and Sustainable Supply Chains (to be published in 2025).

1. Joint commitment to human rights and environmental due diligence (HREDD)

Buyer and Supplier each covenants to establish and cooperate in maintaining HREDD processes in accordance with the standards set out in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) and Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development's (OECD) Guidelines. The HREDD processes shall be appropriate to each party’s size and circumstances.

2. Buyer’s obligations to support HREDD

As part of its HREDD Obligations and to support Supplier’s performance of its HREDD Obligations, Buyer shall engage in responsible purchasing practices. Buyer shall seek to obtain regular feedback from Supplier on its purchasing practices [annually][twice a year]. Responsible purchasing practices include:

Reasonable Assistance. If the parties’ HREDD determines that Supplier requires assistance to perform its HREDD Obligations, Buyer shall provide reasonable assistance, which may be financial or non-financial and which may include cost-sharing, Supplier training, upgrading facilities and strengthening management systems.

Pricing. Buyer shall collaborate with Supplier to agree on a contract price that accommodates the costs associated with upholding responsible business conduct, including the payment of [the minimum wage][a living wage or a living income] and health and safety costs, at a standard at least as high as required by applicable law [and International Labour Organisation norms]. [If the payment of a living wage or a living income is not immediately feasible, then the parties shall develop and commit to a progressive pricing schedule to pay a living wage or living income with [_months][_years].

Modifications. For any material modification (including, but not limited to, change orders, quantity increases or decreases or changes to design specifications) requested by Buyer, the parties shall consider the potential human rights impacts of such modification and take action to avoid or mitigate such impacts. Such action may consist of, for example, adjusting the price or production timeline for the order in question.

Positive incentives: Buyer shall set clear benchmarks to assess HREDD performance and, where feasible, reward performance that exceeds such benchmarks with contract extensions or renewals. In determining whether to continue or expand the commercial relationship, Buyer shall give weight to HREDD performance [equal][as well as] to other criteria, such as quality, price and timely delivery.

3. HREDD default and remediation

Failure to meet an HREDD Obligation constitutes a default ("HREDD Default") that must be [remediated][addressed through a Prevention or Corrective Action Plan]. If the HREDD Default is not remediated (cured) within [_weeks][__months] after receipt of a written notice from the other party, such failure shall constitute a breach of this Agreement. The parties shall cooperate to cure the HREDD Default.

Example model contract clauses to include in your contracts.